While it’s a tough fight to call, some will say satellites have the edge, I have to give it to weather radars for being the final boss when it comes environmental remote sensing. For thirty years radars have been stoically monitoring the skies over America; Warning of us impending disasters, providing a realtime map for meteorologists, and dropping scientific breakthroughs like their hot.

For all their awesomeness though, working with the data can be challenging. At least for me, the biggest blockers aren’t the obvious technical hurdles, but the ol’ gray matter upstairs. Radial projections, aberrations from attenuation, and the daunting amounts of math one must traverse to get the data into something recognizable to humans can leave even the most intrepid data wranglers lost. Which brings to today’s topic, the ground truth I reach for when I’m debugging or testing models that look at radar data: Storm Prediction Center Hail Reports.

Nothing perks up a radar quite like hail, and lucky for me, lobs of ice falling from above also sparks excitement on the ground. Despite getting hit in the head with ice being at least a mildly-traumatic event, and having to repair dents or a roof a moderate one, it seems like a fluent log of these things somehow eluded scientific record.

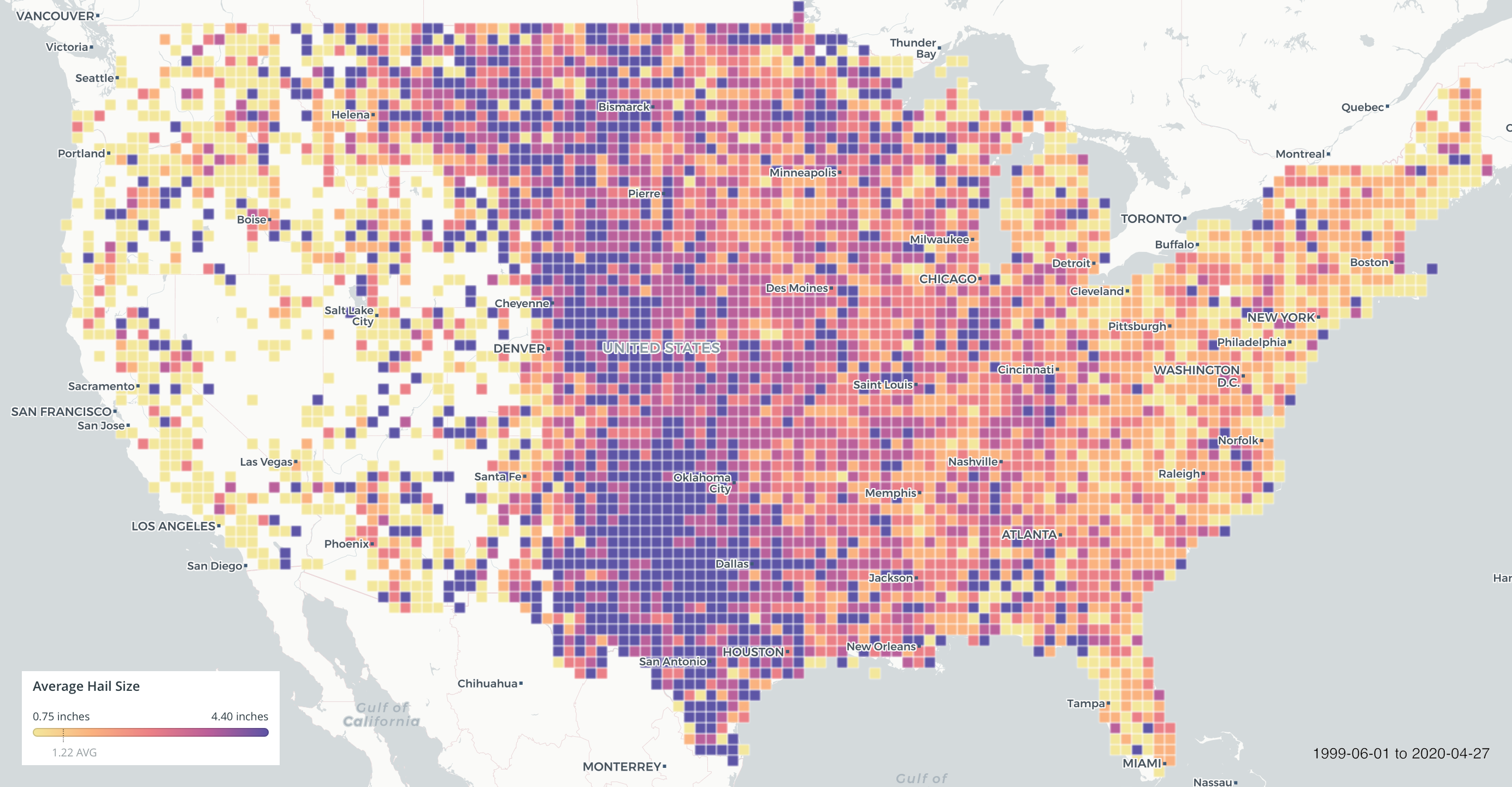

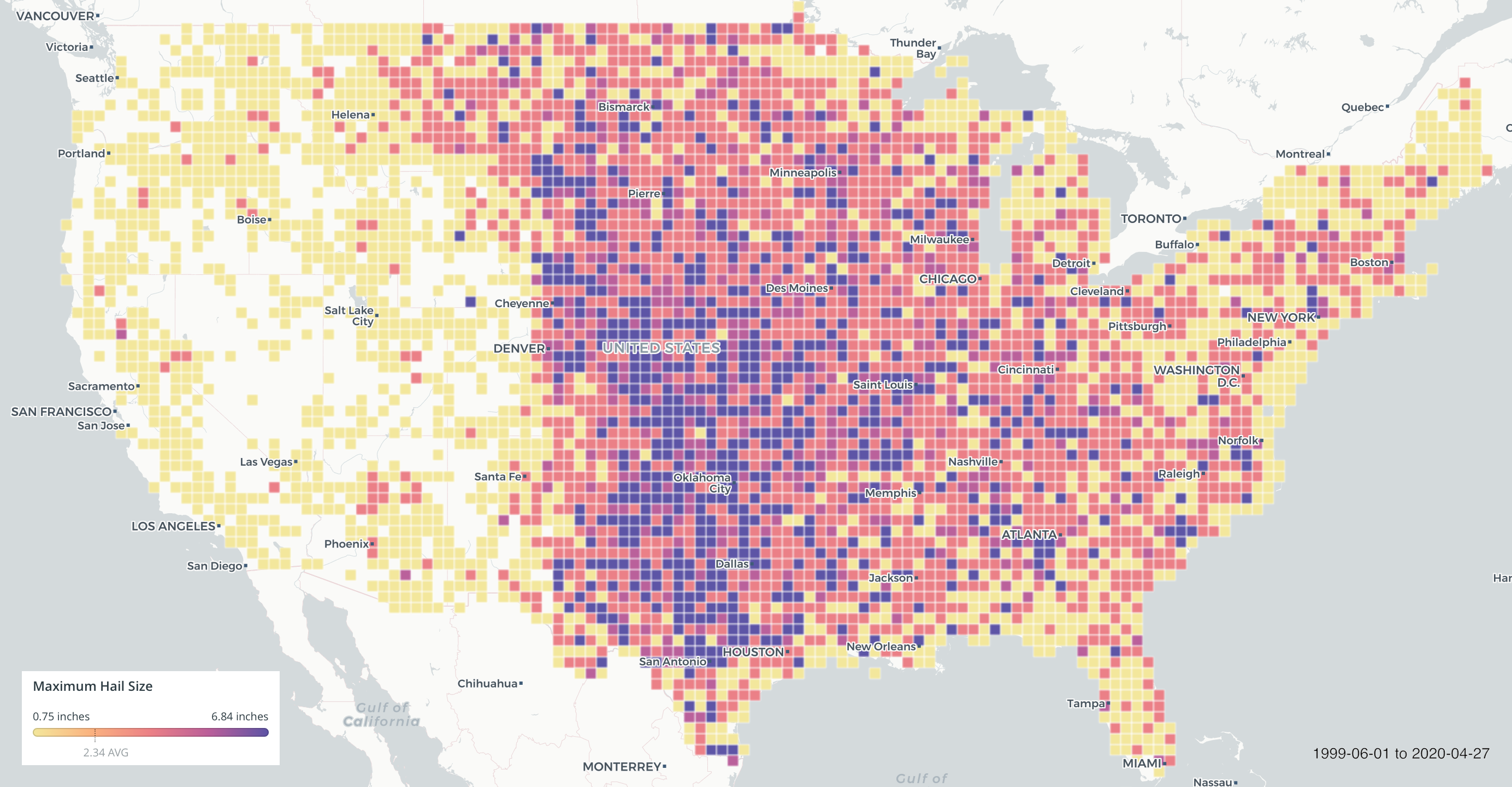

In 1999 The folks at NOAA recognized the potential of writing these things down and started logging storm reports at the Storm Prediction Center. Powered by a network of weather spotters and chasers on the lookout, these reports finally gave us the records needed to tie the ground to the clouds. Obviously, less populated areas are under represented, and data quality issues crop up now and again, but overall, the archive is very usable and has advanced hail science light-years. Another consideration is that data confidence decreases as ice crystal size decreases due to small hail not being reported as often as exceptional events. This data is for working meteorologists mainly concerned about safety and damage, with data science being further down the list of priorities. In other words, your small ice formation model isn’t necessarily invalid if it’s missing verification from these reports.

Beyond weather models, I love this dataset for testing generic geospatial applications. It’s simple, just a handful of columns, 160k fit in a 20mb CSV, has a time dimension with seasonality, and spans nearly every corner of the continental US over twenty years.

Really the only drawback is data archive access through the NOAA’s thoroughly dated website. Some wrangling is required, especially for older data. If web scrapers are in your vocab then it’s easily within reach, otherwise it can be a climb. The scripts I used to fetch data for these maps is available on GitHub.